First published in the journal of the University of Limerick History Society, History Studies, vol.6 (2005), pp.2-17.

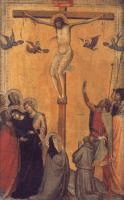

The small fourteenth-century Florentine panel in the Hunt Museum, Limerick, shows an image of the Crucifixion. Beside the cross the Virgin falls in a swoon, supported by one of the holy women and St John the Evangelist. At the other side of the cross the Roman centurion and soldiers are seen. Kneeling at the foot of the cross is St Clare (d.1253), recognized by her Clarissan nun’s habit and halo, and beside her is a Franciscan friar who does not have a halo. Very little is known about the panel: it is, despite its gold background, painted in a realistic manner with bulky figures and little Byzantine like stylisation. The figures show the clear influence of Giotto (1266-1336) and the panel is in fact attributed to the shop of one of his pupils, Bernardo Daddi (d.1348). The dominant position of St Clare and the Franciscan friar indicate that it probably originated from a Clarissan convent or Franciscan friary and the small scale of the panel suggests that it was the side wing of a triptych.1

The small fourteenth-century Florentine panel in the Hunt Museum, Limerick, shows an image of the Crucifixion. Beside the cross the Virgin falls in a swoon, supported by one of the holy women and St John the Evangelist. At the other side of the cross the Roman centurion and soldiers are seen. Kneeling at the foot of the cross is St Clare (d.1253), recognized by her Clarissan nun’s habit and halo, and beside her is a Franciscan friar who does not have a halo. Very little is known about the panel: it is, despite its gold background, painted in a realistic manner with bulky figures and little Byzantine like stylisation. The figures show the clear influence of Giotto (1266-1336) and the panel is in fact attributed to the shop of one of his pupils, Bernardo Daddi (d.1348). The dominant position of St Clare and the Franciscan friar indicate that it probably originated from a Clarissan convent or Franciscan friary and the small scale of the panel suggests that it was the side wing of a triptych.1

This article does not seek to prove the panel’s authorship, secure its exact date, or place it within the oevure of Bernardo Daddi and his shop. For the purposes of this discussion the author accepts that the panel is Florentine and influenced by the work of painters such as Giotto, Taddeo Gaddi (1300-1366) and Bernardo Daddi. Instead, this article will seek to place the iconography of the panel within the framework of devotional iconography, the role of women within late medieval piety and female attitudes towards the Crucifixion, the Eucharist and the body. With the exception of St Clare’s presence – to which I shall return later – there is nothing unusual about the iconography depicted here. The focus on the suffering, dying Christ is typical of the late medieval interest in the pains of the Passion which replaced an earlier iconography of Christ triumphant on the Cross.2 The iconography of the Crucified Christ with angels catching blood from his wounds with chalices is clearly Eucharistic, reminding the viewer that the body and blood of Christ would be consumed in the form of Communion during the Mass said in front of the altar. Frequently in Crucifixion scenes like this, St Mary Magdalen is depicted clutching the bottom of the cross, but in Franciscan imagery she was often replaced by St Francis. Here instead she is replaced by St Clare and not the male St Francis, patron of the friar’s own order. The small scale of the Franciscan friar and St Clare, and their anachronistic presence transform a narrative scene depicting a scriptural event into a devotional one where the viewer is invited to contemplate the Crucifixion as they do.

St Clare and the friar are explicit signs of the Franciscan order but Franciscan ideals are implicit in the overall imagery of the panel. The late middle ages saw what has been characterized as an ‘explosion’ of lay piety and new devotional movements. Influenced by developments such as the papal reform of Gregory VII (c.1081-85) and the writings of individuals such as the Cistercian St Bernard of Clairvaux (d.1153), devotion began to centre upon the a human, suffering Christ instead of Christ the Judge.3 The growth of a cult to the Virgin Mary was closely tied to these developments and to Bernardine writings. Emphasis shifted from a sacramental and often remote religion to one where the laity was encouraged to meditate on and emphathise with the Gospel narratives. St Francis (c.1181-1226) – who was himself both a product of and an influence on this piety – led a life in which he imitated, as literally as possible, the life led by Christ.4 For Francis this meant absolute poverty and the renunciation of all possessions, summed up by both his critics and supporters as the vita apostolica or apostolic life. Francis’ life also involved emotional involvement in the sufferings of Christ and the humanity that Christ redeemed, and a love of the natural world as a sign of God’s creation. The imitation of Christ practiced by Francis of Assisi was rewarded by the physical imprimatur of God’s approval. In 1224, while staying at the remote hermitage of la Verna in Tuscany, Francis received the five wounds of Christ on his own body and became the first saint in church history to bear the stigmata.5

Although the original ideals of Francis were soon compromised by the growth of a large religious order, the Franciscans maintained an emphasis on emotionally involving oneself with the life of Christ through prayer, meditation and imitation. The Franciscans, and their fellow Mendicant Order, the Dominicans, also emphasised spreading the word of God through preaching in the vernacular in market squares and other public places in the city states of medieval Italy.6 Unlike earlier religious orders which had based their regimes on seclusion from the world, the Franciscans and Dominicans usually settled on the industrial working class outskirts of cities in order to preach to as wide an audience as possible. Popular preachers such as the Franciscan St Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444), the Dominican Fra Giovanni Dominici (1355-1419), and, perhaps most famously, Fra Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498), repeatedly filled great cathedrals and urban spaces with crowds. Their sermons were simple, direct, entertaining, and frequently fiery.

Typical of this new ‘affective’ piety were new devotional texts, often instructing the reader or listener (for texts were often read aloud) in religious history and advocating that the reader/listener imagine him/herself to be physically present at narrative stages in the life of Christ or the Virgin. One such text was the Meditations on the Life of Christ, for a long time attributed to the Franciscan saint, Bonaventure (1221-1274). This was diffused widely and emphasised a direct emotional relationship between the reader/listener and the figures of the narrative. Written for a Clarissan nun, it advised the reader to imagine such scenes as her holding the Christ Child against her cheek.7 The text is essentially a narrative of the Life of the Virgin and Christ, interspersed with direct invocations to the reader to imagine herself present at the scenes and to involve herself emotionally as a participant. Homely details are used in order to make the religious events described as real as possible. For instance, when narrating the disappearance of the twelve year old Jesus, the author invokes the landscape of his native Tuscany:

Very early the next morning they left the house to look for Him in the neighbourhood, for one could return by several roads; as he who returns from Siena to Pisa might travel by way of Poggibonsi or Colle or other places.8

Stern warnings are given to the nun to imitiate the life of the Virgin in a typically Franciscan reference to poverty and humility:

‘Did the Lady, whatever she worked on, make for love some fancywork? No! These are done by people who do not mind losing time. But she was so poor that she could not and would not spend time in a vain occupation, nor would she have done such work. This is a very dangerous vice. Especially for such as you.9

The emotional demands made upon the reader are increased with the account of the Passion, with much of it written in the present tense:

She is saddened and shamed beyond measure when she sees Him entirely nude: they did not leave Him even his Loincloth. Therefore she hurries and approaches the Son, embraces Him, and girds Him with the veil from her head.10

The image of the swooning Virgin Mary – which was frequently used by artists of the period – in the Hunt panel can be traced to the Meditations, where the author recounts how after the side of Christ has been pierced, ‘the mother, half dead, fell into the arms of the Magdalen’.11

Great article Catherine and, in keeping with the subject, a meditational piece in itself .

Keep up the good work, and as Clare’s brother Francis said:

Preach the Gospel at all times and when necessary use words.

Thank you so much for your kind comment. Best, C.