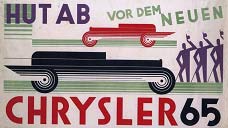

The 1926 British advertisement was a representation of a Chrysler car zooming into the foreground, its trajectory accompanied with diagonal lettering. The 1929 version broke down the cars formal elements of wheels and chassis in a series of parallel diagonals, forming an abstract machine aesthetic which emphasised the cars power and speed, demonstrating in particular elements of Bauhaus design [Fig 5]. Similarly, his 1927 work for British Petroleum makes use of this diagonal setting in the brand name, “BP”, while the car moves along a horizontal line within a triangle of blue. The effect of bold colour, line and shape is reminiscent of Constructivist graphics.

As in America at this time, Havinden was associating modernist styles with commercial brands. In his automotive advertising, he drew from the suitability of these styles which in turn took their inspiration from the machine aesthetic. The object of production, here the automobile, is obviously the intended focus of these advertisements. What is important is the recognition and application of these modernist abstract styles which originate in the tools of mass-production and at the same time promote the fruits of mass-production.

Mass culture is commented on broadly in Pop art, the style which rarefied and elevated the manufactured object to high art. Eduardo Paolozzi was seen to belong to the British school of Pop, most probably because of his tireless lifting of the everyday object – manufactured or otherwise – into his art. His work makes heavy use of the machine aesthetic. Paolozzi’s collages became an interesting take on the Pop ethos, transferring an image from one context to another. He has also been seen as part of the European Surrealist movement, and this variety of movements to which he has been said to belong reflects the huge variety of style, method and medium evident in his work. In conventional collage works depicting objects from advertisements and mass culture, this classification of Pop art fits, but his ‘collage’ of material in other mediums, such as sculpture, constructs improbable figures that look like surreal machines.

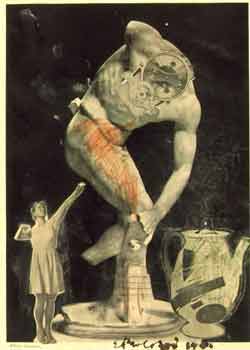

Distorted pictures of antique sculpture appear in earlier work, illustrating the suitability of collage to deform and misshape. Discobolus of the Castel Porziano, 1946, [Fig. 6 ] a model of classical sculpture, taken from a Hadrian age replica, is superimposed with cogs and wheels, rendering the statute in a hybrid state. Paolozzi’s own sculptures from the 1950’s exhibit a dual exploration of the machine/human, representing the form through two possibilities. The first type has the appearance of an abstract set of shapes, containing formal elements that could be arranged in different combinations. The other type is figurative, with a form reliant on the structure it is given, like the human being or built machine; unlike the abstract type, its elements do not have the scope to be moved around. The Philosopher, from 1957, is one such figurative piece. The bronze sculpture was created by constructing a frame out of wax sheets which were impressed with mechanical shapes like cogs, wheels and ambiguous mechanical forms, compiled and standing on two legs. While this style correlates to his construction of things through the concept of collage, its overall effect is to comment that while the mind may arrange and change structures, the body itself cannot be altered.

Paolozzi's relief sculpture for the Cleish Castle Ceiling [1970-73], [Fig. 7] appears today in eight panels, housed in the National Gallery of Modern art in Edinburgh. It is made up of separately conceived elements that work together, while possessing the possibility to interrelate in a different arrangement. In a reproduction of the artist’s London studio, these elements appear constructed in plaster, like separate parts of a jigsaw puzzle that would assist in deciding their combinations. The machine aesthetic is used in such relief sculptures, but serves as a medium to refer to the artist’s fascination with the interplay of shadow and light in Classical relief carvings [5], a fact which allows the machine aesthetic to transcend its contemporary context.

Calcium Night Light,1974-76, appears at first glance to be an abstract representation of the inner workings of a machine, but when taken and compared to other works in the series, it becomes clear that it is rather the machine aesthetic that dominates. Formal elements of the screen print which include cogs and wheels, curving cable like shapes and stripes, appeared in the Cleish Ceiling. While the relief format of the ceiling allowed the machine aesthetic to thrive in metallic form, the screen prints provided new possibilities for the aesthetic, through colour.

Paolozzi is said to have brought all human experience into one huge collage [6]. This conveys the idea that his work is best approached by keeping in mind the characteristics of collage. The machine aesthetic proved useful in Paolozzi’s work. It provided the artist with a visual language with which he could define his constructed elements, and also allowed them to be better understood as manufactured objects, fitting together to make broader comments about the consumer-led society to which they and he belonged.

Machine inspired art from the twentieth century has followed the progress of society but it has also borrowed from previous interpretations of the machine aesthetic in art. At the beginning of the century, the Futurists experienced a sharp shift in the perception of the world, visually through its interpretations in cubism and viscerally through the extended plains of possibility which the machine age offered. The world was emerging from itself, and the machine age represented freedom from the confines of previous human experience. The absence of war throughout the formative decades, in the industrial revolution, contributed to the cult of machine achieving a central status in European art in the first twenty years of the twentieth century. In the 1920s and 1930s, manufacturers sought to associate their machine made products with the artistic movements which had risen out of this cult of machine. The role of the machine in twentieth century art was therefore a reciprocal one. After the second world war, the full implications of mans inhumanity to man through the machine became clear, and the new associations which rose from this come through to a certain extent, in Paolozzi’s work. This essay has not dealt with the major art movements in relation to the sociological conditions which precipitated them. Conversely, it has traced the influence of the machine in art as it appears in the image, and accounted for the discussion and use of the machine aesthetic in art

Notes:

[1] Judy Davies, ‘Mechanical millennium: Sant’Elia and the poetry of Futurism’, in Edward Timms and David Kelley (eds.) Unreal City: urban experience in modern European literature and art. (Manchester, 1985) pp. 66-73.

[2]Nicole Armour, ‘The Machine Art of Dziga Vertov and Busby Berkeley’ Images Journal, Issue 5 http://www.imagesjournal.com/issue05/features/berkeley-vertov.htm Accessed, 23.05.05).

[3] Jennifer Pricola ‘Art for Trades Sake, The Fusion of American Commerce and Culture 1927-1934’. American Studies, University of Virginia, 2003 (http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA03/pricola/art/intro.html Accessed 24.05.05).

[4] Michael Havinden ‘Life and Work’ in Advertising and the Artist, Ashley Havinden (Edinburgh: Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland, 2003) p. 15.

[5] Michael Spens Introduction to ‘Eduardo Paolozzi, Writings and Interview’ in Studio International (http://www.studio-international.co.uk/reports/PaolozziE_10_5.htm Accessed 24/05/05).

[6] Ibid.

Bibliography

Armour, Nicole, ‘The Machine Art of Dziga Vertov and Busby Berkeley’ Images Journal, Issue 5 (http://www.imagesjournal.com/issue05/features/berkeley-vertov.htm Accessed 23.05.05);

Davies, Judy, ‘Mechanical millennium: Sant’Elia and the poetry of Futurism’, in Edward Timms and David Kelley (eds.) Unreal City: urban experience in modern European literature and art. (Manchester, 1985) pp. 66-73;

Havinden, Michael, ‘Life and Work’ in Advertising and the Artist, Ashley Havinden (Edinburgh: Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland, 2003) p. 15;

Hughes, Robert The Shock Of The New: Art and the Century of Change London: Thames and Hudson, 1991;

Pricola, Jenifer ‘Art for Trades Sake, The Fusion of American Commerce and Culture 1927-1934’. American Studies, University of Virginia, 2003 (http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA03/pricola/art/intro.html Accessed 24.05.05);

Spens, Michael, Introduction to ‘Eduardo Paolozzi, Writings and Interview’ in Studio International (http://www.studio-international.co.uk/reports/PaolozziE_10_5.htm Accessed 24/05/05);

The Irish Museum of Modern Art Catalogue of the Collection May 1991 – 1998 ed. Catherine Marshall and Ronan McCree Dublin: IMMA, 1998.